How to Fight Climate Change, Promote Community Economic Development, and Finally Close that Nasty Incinerator: Remove food waste from the Baltimore school and university waste stream

Executive Summary

Baltimore is poised to make great strides towards the goals of creating good jobs and ending harmful environmental practices. When we combine the vision of our world-class education institutions, the passion of South Baltimore community activists who never gave up, and the leadership of city elected officials, we will do several incredible things:

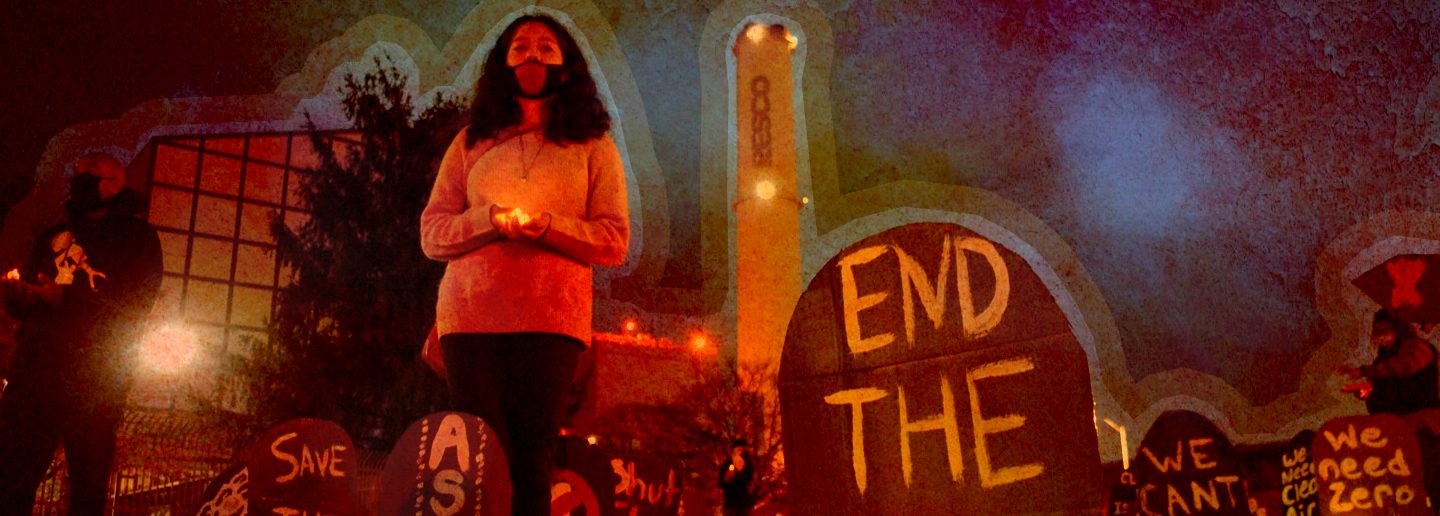

- We will put to rest our health- and environment-destroying trash incinerator;

- We will slash our greenhouse gas emissions; and

- We will create good jobs for those who need them most.

We will do this by separating food waste from the solid waste stream of educational institutions to keep it out of landfills and incinerators, and composting it at a new South Baltimore facility.

We have been on the brink of making this happen for several years, and now the last piece has been put into place by the Maryland legislature’s newly passed Food Waste Diversion Act. The Act has requirements we have the ability to meet by its effective date of January 1, 2023.

Our state, our country, and our planet are facing an existential threat from the climate crisis. At the same time, we are recovering from a global pandemic that has worsened economic inequalities for our working-class and poorest communities. Meanwhile, decades of disinvestment and environmental racism have left Black communities needing development, while our farmlands need regeneration. We have an opportunity to take a single bold step to begin food waste separation and composting, which gives us solutions to multiple problems.

Taking this step will allow Baltimore to:

- Significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Food waste, which is 40% of the waste stream, creates methane gas when it decomposes in landfills and creates carbon dioxide when incinerated. Methane and CO2 are the two main greenhouse gases that are causing the climate crisis and global warming;

- Turn food waste into nutrient-rich compost that helps fertilize crops, keeps the soil rich, and replaces harmful chemical fertilizers;

- Create a new business sector with good, family-supporting jobsin traditionally under-invested working-class, poor and Black communities;

- Abide by the new Maryland law that will require large-scale food waste producers to separate food waste from their waste stream;

- Help Baltimore’s Department of Public Works and Office of Sustainability meet their goals to remove food waste from the waste stream; and

- Partner with Johns Hopkins and other universities and local institutions that are committed to getting organics out of their waste streams.

A wide-ranging coalition of community groups, colleges and universities are on board with this proposal. We are asking the City of Baltimore to assemble a group of stakeholders to work on a planning document, with the goal of having a food waste collection process and composting facility online in Baltimore by 2023.Climate Change and Food Waste

Our planet is heating rapidly. Addressing climate change and reducing greenhouse gas emissions is a major priority in Maryland. When food waste is disposed of in landfills and incinerators with the rest of our trash, its decomposition leads to greenhouse gas emissions in the form of methane and carbon dioxide. Meanwhile, Maryland recently discovered that four times as much methane is leaking out of its landfills than previously thought.

Several state laws now require Maryland to have a statewide climate change plan, make significant greenhouse gas reductions, and create new jobs as part of this work.

Food waste makes up 40% of the waste stream, and several hundred thousand tons of food are sent to landfills or incinerators every year in the Greater Baltimore area. Baltimore’s Department of Public Works and its Office of Sustainability both have stated goals to remove food waste from the city’s waste stream. Separating out food waste:

- Keeps it out of incinerators and landfills, where it pollutes the air of adjacent communities and creates greenhouse gases;

- Makes it easier and cheaper to separate non-food recyclables;

- Allows us to create nutrient-rich compost that will help farmers and urban gardens fertilize their crops and keep the soil rich, replacing harmful chemical fertilizers. Compost cheaply and effectively stops the production of methane and helps our soil move CO2 out of the atmosphere and bury it in the soil where it provides important nutrients for the food we eat;

- Would give us an opportunity to use the compost in planting flora that removes greenhouse gases from the atmosphere;

- Can lead to community transformation by providing good union jobs that are secure and permanent and can support families; and

- Make it unfeasible for the BRESCO incinerator to stay open.

We estimate that the education institutions – colleges, universities and K-12 public schools – in Baltimore City and County dispose of approximately 150,000 tons of food waste each year. These institutions currently either compost at a very low level or mix food waste with trash which ends up in landfills or the BRESCO incinerator.

The common-sense first step is to create a food waste collection and composting project for the local education institution sector, and in the process, create a model for other localities to abide by the Food Waste Diversion Act.

Compliance with Maryland’s Food Waste Diversion Act

Educational and other major institutions in Baltimore still mostly throw out food waste with their trash, which ends up in landfills or at the BRESCO incinerator. There is a small amount of composting, and much of the food waste that is composted is currently hauled to the Prince George’s County Organics Compost Facility, more than 40 miles outside of Baltimore. No permitted composting facility currently exists in Baltimore City, though a private facility may be coming online later this year in Baltimore County.

A new state law passed in 2021, known as the Food Waste Diversion Act, requires large-scale food waste producers to reduce, donate or source-separate their food waste if an organics recycling or composting facility is within a 30-mile radius and has the capacity and is willing to accept the waste.

The law specifically covers local school systems and nonpublic schools; supermarkets, convenience stores, mini-marts, business, school, or institutional cafeterias; and cafeterias operated by or on behalf of the State or a local government. The law begins to phase in on January 1, 2023.

Food Waste Processing in Baltimore

Most entities covered by Maryland’s Food Waste Diversion Act will find it challenging to develop from scratch a local food waste collection and processing system that will allow them to comply with the new law. In Baltimore City, our Mayor, City Council, community organizations and institutions have become strong drivers of Baltimore’s Zero-waste policy and have anticipated this transformation. What will be a challenge to other localities in Maryland has become an opportunity for Baltimore’s elected officials and communities to transform rapidly to its zero-waste system and be pioneering leaders in the development of this promising new sector of the economy. The first step will be to build composting and specialized food waste collection infrastructure capable of processing organic waste from the higher education institutions in and near Baltimore City and County. Later on, this system could include collection and processing for all commercial food waste.

In addition, no single institution generates the scale of food waste needed to make a collection/processing venture sustainable. Moreover, there is no certified food composting facility in Baltimore City ready to handle this challenge. Multi-institutional procurement will need to be created amongst universities, colleges and schools to achieve the economies of scale necessary to justify the creation of a reliable and cost-effective food waste collection and processing infrastructure. Universities have discussed collective procurement to support new composting/recycling infrastructure in the past but have not yet done so. A coalition of local colleges and universities (Appendix A) has been organizing around sustainability initiatives, and coalition members say they would like to be part of a collective composting project.

Economic development in South Baltimore: Siting food waste processing facilities there

Located in Curtis Bay, South Baltimore, the former Pennington Avenue Landfill is a 64-acre city-owned site that closed in 1981. It is situated in a mixed industrial/commercial/residential area of Baltimore City [Appendix B]. Baltimore’s Department of Public Works has identified this site as having potential for repurposing as a composting facility and is currently conducting an assessment.

After a decade of grassroots organizing, South Baltimore communities coalesced around the idea that they can address the serious needs of their communities by creating the South Baltimore Community Land Trust (SBCLT). The SBCLT is a group of community leaders and activists in Curtis Bay who are preparing for a community master planning process. The SBCLT sees a food waste processing and composting facility as a way to generate good union jobs and create sustainable economic development in surrounding economically underdeveloped communities.

With the help of the Mayor of Baltimore, the new DPW Director, the Baltimore City Council, many of the largest and most prestigious institutions in Baltimore, and with support from organized labor, SBCLT is ready to champion and help implement a plan creating a food waste collection and compost-processing system to serve the major institutions that generate large volumes of food waste.

Conclusion

Food waste makes up 40% of the solid waste stream. Incinerating or landfilling this waste creates toxins that harm the public’s health and creates greenhouse gases that are a major cause of the growing climate crisis. Recent legislation requires us to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and to figure out how to recycle our food waste.

It has been demonstrated that when we remove food and other organics from the waste stream, and process it into valuable compost, we can promote healthy, locally-grown food and sequester large amounts of carbon dioxide from our atmosphere. These efforts can also be an engine of economic growth for the local economy: creating good union jobs for our communities, boosting nutrient-rich locally grown food, and attracting local businesses into South Baltimore – all the necessary elements to grow a thriving community-based economy.

The SBCLT is the vehicle for a community-led just transition away from an unhealthy community of toxic hazards, unsafe and unaffordable housing, and dead-end low road jobs, into a community-led economic development model based on the core values and principles of human dignity, environmental stewardship, democratic governance, justice, and equity.

After years of work establishing strong bonds between community leaders, elected officials, important Baltimore institutions, organized labor, and leading national zero-waste experts, SBCLT and its allies are ready to take the next step in realizing their goal of sustainable community development.

We ask the City of Baltimore to partner with SBCLT, local education institutions and workers’ unions to create a food waste collection and compost processing system for the primary schools, colleges and universities located in the Greater Baltimore area. This would be an incredible and innovative first step that would make Baltimore a leader in Maryland and allow us to expand the program to other producers of food waste and follow the Maryland Food Waste Diversion Act.